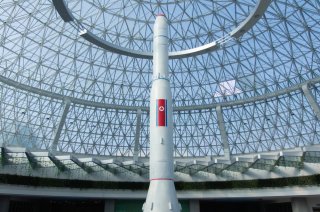

Kim Jong-un Has Fewer and Fewer Reasons to Give Up His Nuclear Program

The DPRK’s Nuclear program is increasingly and structurally entrenched by forces internal and external to the regime.

The DPRK believes it needs nuclear weapons to offset its vulnerability to the U.S. nuclear capability and to compensate for the weakness of its conventional military forces relative to those of South Korea. Those problems would return if North Korea dismantled its nuclear weapons program. The war in Ukraine offers Kim a fresh example of how hostile great powers prey on non-nuclear-armed countries. Ukraine gave up its Soviet-deployed nuclear weapons based on security guarantees from Russia and the West.

Nuclear weapons give North Korea prestige. Kim’s government has invested heavily in making nuclear weapons an essential part of the regime’s legitimacy and the country’s self-image. Nuclear weapons reinforce the notion, crucial to the narrative that helps keep the regime in power, that the superpower United States is bent on destroying North Korea, thwarted only by the extraordinary leadership of the Kims. Nukes represent a technical accomplishment that puts a poor and weak North Korea into the small international club that includes the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Acquiring nukes got Kim meetings with the leaders of the United States and China.

Recent statements by the regime explicitly state the nuclear weapons program is permanent and will never be on the bargaining table. Perhaps more significantly, the Kim regime is moving beyond a minimum deterrence strategy by expanding its inventory of nuclear bombs and diversifying its delivery systems. With each passing day, the DPRK sinks more resources into its arsenal of nuclear missiles, making a turnaround harder and less likely.

The possibility of North Korean denuclearization is decreasing with the passage of time. With the establishment of the nuclear weapons program, groups of North Korean elites that benefit from its presence become more firmly established. These groups would act as bureaucratic obstacles to any attempt to shutter or wind down the program.

The larger geopolitical trends are unfavorable to North Korean denuclearization. The bifurcation of Northeast Asia into two competing blocs has tightened and hardened. Since it invaded Ukraine, Russia has grown closer to both China and North Korea. Pyongyang and Moscow are exploring new areas of economic and technical cooperation. This reduces the DPRK’s international isolation and enlarges the country’s economic safety net, increasing the Kim regime’s ability to weather U.S. sanctions and correspondingly undercutting the power of those sanctions to compel Pyongyang to bargain away its nuclear weapons. At the same time, the deterioration in relations between the United States and the China-Russia bloc minimizes any incentive in Beijing and Moscow to be tough on Pyongyang as a favor to Washington.

The Trump-Kim meetings in 2018 and 2019 suggest negotiations over denuclearization could resume, especially if Trump gets re-elected president. Keep in mind, however, that the last round of talks in 2019 failed spectacularly; bilateral relations remained poor thereafter for the remainder of the Trump presidency; it was never clear that Pyongyang intended to actually denuclearize, as opposed to selling off unimportant parts of its nuclear weapons infrastructure to gain relief from U.S. sanctions. Any denuclearization agreement would face immense implementation hurdles involving transparency and verification.

The chances of the DPRK giving up its nuclear weapons are not zero, but realistically this could only happen in a future world with radically changed conditions.

Denny Roy is a Senior Fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, specializing in Asia-Pacific strategic and security issues. He holds a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Chicago and is the author of Return of the Dragon: Rising China and Regional Security (Columbia University Press, 2013), The Pacific War and its Political Legacies (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2009), Taiwan: A Political History (Cornell University Press, 2003), and Chinas Foreign Relations (Macmillan and Rowman & Littlefield, 1998), co-author of The Politics of Human Rights in Asia (Pluto Press, 2000), and editor of The New Security Agenda in the Asia-Pacific Region (Macmillan, 1997). He has also written many articles for scholarly journals such as International Security, Survival, Asian Survey, Security Dialogue, Contemporary Southeast Asia, Armed Forces & Society, and Issues & Studies. He tweets at @Denny_Roy808.

Image: Shutterstock.