China's Nationalist Heritage

Mini Teaser: Chinese leaders have reverted to a pre-Communist ideology of national rejuvenation. This could complicate foreign affairs.

Turning to Greenfeld’s second dimension, China’s various ideologies and traditions portray citizenship, on balance, as a matter of ethnic rather than civic belonging. Officially, Marxism and Maoism preach equality, including across ethnic lines. But traditional Confucianism emphasizes birth circumstances and ancestry: “I have heard of barbarians being transformed by Chinese. I have never heard of Chinese being transformed by barbarians.” At the end of the nineteenth century, the founding generation of Chinese nationalists blamed Confucianism for the Qing dynasty’s weakness and sought to replace it. But as discussed above, Sun Yat-sen and others returned from exile in Japan impressed by Japanese ideas of race. Granted, Sun lived to discover the inconvenience of his notion that “the greatest force is common blood.” Once he set about the task of trying to govern China after the fall of the last Qing emperor in 1911, it proved unwise to exclude those not descended from the Yellow Emperor in the “Three Principles of the People.” Sun was now trying to lead not only Han Chinese but also Manchus, Mongols, Tibetans and Muslims. To help unify the territory that had belonged to the Qing, he proceeded to develop an idealization of the “union of five races”—Han, Manchu, Mongol, Tibetan and Hui (Chinese Muslim)—that has been carried on by successive CCP chiefs to this day.

Do traditional notions of Han lineage trump later efforts to forge a common, transethnic identity in China? The Hong Kong–based historian Frank Dikötter contends that “Chineseness” in contemporary China is “primarily a matter of biological descent, physical appearance and congenital inheritance.” He cites a passage from He Shang (River Elegy), a popular 1988 television miniseries written by the son of a high-ranking party member:

This yellow river, it so happens, bred a nation identified by its yellow skin pigment. Moreover, this nation also refers to its earliest ancestor as the Yellow Emperor. Today, on the face of the earth, of every five human beings there is one that is a descendant of the Yellow Emperor.

Under Mao, tracing the nation to the Yellow Emperor would have been forbidden as a relic of Confucianism, but pre-Communist perceptions and impulses are now resurgent. China has not produced any kind of melting-pot ideal that would allow non-Han people to share the traditions of the Chinese nation. At best, the party seems to have adopted a mixed approach to China’s ethnic minorities, combining in rhetoric and practice elements of egalitarianism, paternalism and exploitation. The three main lessons about ethnic minorities offered in current Chinese high school textbooks revolve around encouraging them to “overcome superstition” (i.e., their religious beliefs), harnessing their “contributions” (e.g., oil from Xinjiang and pastoral products from Mongolia), and receiving their “gratitude” for the civilizing role of the Han population. Traces of older ideas about bloodlines and racial value thus remain apparent in the CCP’s less than fully tolerant approach to minorities.

Chinese contacts are sometimes candid in explaining to foreign visitors the logic behind the official encouragement of, and provision of incentives for, Han resettlement in Tibet and Xinjiang (home of the Uighur Muslim minority in western China). A friend of the author was recently told by a Han security officer in Xinjiang: “Once we have achieved a 9 to 1 ratio of Hans to Uighurs, our problem will be solved.” Similarly, Western travelers to Tibet these days often hear from locals that the party is trying to extinguish their culture.

SETTING ASIDE any judgments of Beijing’s policies as illiberal or inhumane, the conditions fostered by these policies have generated deep-seated insecurity for CCP leaders. In virtually every speech and document from the party, reference is made to the unification or great unity of the country, including minorities, usually in connection with the rejuvenation project. The effort to conjure an image of past and future Chinese greatness is allied to an attempt to depict China as ethnically unified, despite the reality of persistent ethnic tension. Again, Jiang Zemin was an early exponent of the trend. As Zheng Wang, a scholar of Chinese nationalism at Seton Hall, has noted, in a speech in July 2001 at a celebration of the eightieth anniversary of the founding of the CCP, Jiang proclaimed:

We have thoroughly put an end to the loose-sand state of the old China and realized a high degree of unification of the country and unparalleled unity of all ethnic groups. We have abrogated the unequal treaties imposed upon China by Western powers and all the privileges of imperialism in the country.

For those who might have missed the link between strength from unity and rejuvenation, the speech also includes this assurance:

Every struggle that the Chinese people fought during the one hundred years from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century was for the sake of achieving independence of our country and liberation of our nation and putting an end to the history of national humiliation once and for all. This great historic cause has already been accomplished. All endeavors by the Chinese people for the one hundred years from the mid-20th to the mid-21st century are for the purpose of making our motherland strong, the people prosperous and the nation immensely rejuvenated.

Jiang’s successor, Hu Jintao, went even further out of his way to emphasize rejuvenation and unity. His aforementioned 2011 address on the centennial of the 1911 revolution exhorted China to remember that “patriotism is the soul of the Chinese nation and a powerful force mobilizing and uniting the whole nation to strive to revitalize China.” For rejuvenation to succeed, he explained, it is necessary to “foster harmonious relations between ethnic groups, between religions, between social strata, and between compatriots at home and overseas.” The incoming general secretary, Xi Jinping, will inherit not only this rhetoric but also a raft of supporting material, from textbooks to museums, memorials, and even public holidays dedicated to China’s humiliation and renewal, including its achievements vis-à-vis minorities. All of this fanfare has been developed and promulgated over the past two decades, and in an address to the CCP’s Central Party School in 2008, Xi showed that he has been a careful observer of these innovations. After paying homage to the two “historic leaps” that China had made in the past century, in 1949 under Mao and in 1978 under Deng, Xi stated:

The theoretical system of socialism with Chinese characteristics [i.e., the CCP’s system] is the only correct theory by which to carry forward into the future, keep up with the times, and unite and lead the people of all ethnic groups across the country along the road of socialism with Chinese characteristics to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.

Beneath the compulsive repetition of this theme by successive Chinese leaders lies a deep-seated anxiety about the durability of the party’s achievements in the domains of unification, prosperity and international prestige.

The content of contemporary Chinese nationalism helps explain the recent flare-ups between China and its neighbors, as well as with the United States and Europe, over issues that include fishing rights, territorial claims, intellectual-property theft and participation in international climate-change initiatives. Given the chasm between the outlook of CCP elites and that of Western or Westernized nations in the region, such clashes are likely to grow in intensity and frequency. Chinese nationalism will create turbulence for China abroad because its hierarchical, zero-sum perspective is fundamentally at odds with the principles underlying the current global order and because international engagement remains critical to the party’s economic-growth strategy.

Domestically, the elitist and ethnocentric cast of Chinese nationalism pits the party against elements of China’s own population. Hence the ever-rising domestic-security budget, now reportedly higher than spending on the Chinese military, aimed at controlling the growing number of domestic protests, or “mass incidents” in party parlance. From the standpoint of stability, the implications of CCP elites’ reversion to the pre-Communist idea of rejuvenation are mixed. Having abandoned revolution, the party is now casting itself as the heir of Chinese dynasties that ruled over the glory days of Chinese civilization. Throughout Chinese history, however, dynasties rose and then fell, and rejuvenation or restoration was a retrospective way of characterizing and celebrating the peaks in this cycle. The low points involved the dissolution of central authority, invasion by foreign conquerors and, at times, the loss of significant pieces of Chinese territory. Today’s talk of rejuvenation is thus inherently two-sided; it is triumphalist, but it also raises the specter of a potential future in which the current regime will have succumbed to the age-old forces that undermined past dynasties. For the United States, dealing with such a combination of confidence and insecurity in Beijing is likely to be especially difficult.

Jacqueline Newmyer Deal is president and CEO of the Long Term Strategy Group, a Washington-based defense consultancy, and a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

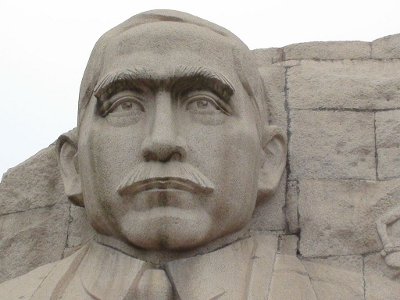

Image: Pullquote: The reality is more nuanced than either the image of European-style fascism or the theory of Chinese democratization, though it is unfortunately closer to the former than the latter. Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: The reality is more nuanced than either the image of European-style fascism or the theory of Chinese democratization, though it is unfortunately closer to the former than the latter. Essay Types: Essay