The U.S. Marines Have One Big Weakness. Here's How to Fix It.

Not what you think.

"Lat[eral] moves for [all aviators] to become a MARSOC [Special Operations Officer] are not being approved" at this time, the email from the Monitor said, adding that "[Inter-Service Transfers] for [any aviator] to any branch, to include the USCG, are not being approved [at this time]."

The email was just the latest restriction on aviators, and the next round of Headquarters Marine Corps' (HQMC) ineffective strategy for dealing with a critical shortage of company grade aviators in the Marine Corps.

The Air Force has garnered most of the attention regarding pilot shortages over the past few years, but it's hardly unique to their service, as the entire military is struggling to keep its aviators in the midst of an airline hiring frenzy and a strong economy. For years, the pilot shortage was attributed to Obama-era sequestration, aging platforms, and a lack of sufficient flight time.

But there is a more significant contributor to this shortage: mismanagement of pilots due to unwritten rules of the aviation promotion system.

Unfortunately for the Corps, company grade aviators catch on to these rules early, and flight school cannot produce enough new pilots to balance the inevitable exodus of captains. If this exodus is not effectively addressed, our ability to fight from the air could be critically compromised in a way that will take decades from which to recover.

So how bad is it really?

As of March 2019, according to the MOS inventory report from HQMC, overall fixed-wing, company grade (O-1 through O-3) aviation strength stood at a staggering 52%. This value encompasses all aviators for the C-130, F-35, F-18, and AV-8B communities.

Rotary Wing and Tiltrotor company grades fair somewhat better at 76% overall with all but one, the AH-1 Cobra Attack Helicopter community, tracking well below the 85% mark of what is considered a "healthy" inventory level, as seen in the table below. The data also shows a worrying trend of over-staffing well above 100% for field grade (O-4 and O-5) in all communities except the struggling MV-22 field.

At this point one might ask, "If the fixed-wing community is so much worse off, why are you focusing on the rotary and tiltrotor communities so much?" The answer: The extreme focus on the shortage of Fixed Wing aviators has distracted from an equally distressing shortage in the Rotary Wing and Tilt-Rotor communities that HQMC is failing to adequately address.

So what is causing this shortage? This is a very complex problem, and while every aviator has their reasons for staying or leaving — ranging from quality of life to financial opportunity — one systematic constant significantly contributes to the current exodus.

The unwritten rule of Marine Corps aviation

"Every one of you should want to be a WTI," was the phrase directed at my peer group during my first month in the fleet. It seemed logical. The CO, XO, OPSO, Aviation Maintenance Officer (AMO), and the Director of Safety and Standardization (DOSS) were all Weapons and Tactics Instructors (WTI).

As the top echelon of the five standard instructor qualifications, WTI is the highest and most difficult designation a pilot or crew chief can achieve, and appeared to be the best way to continue with an aviation career in the Marine Corps. What wasn't told to us back then was that it is the only way to be successful in an HMLA (a composite squadron comprised of both the AH-1 Cobra and UH-1 Huey helicopters).

Something key to know about why it is the only path to success is that there is no official or "standard" career path for an H-1 pilot in any manual or policy. There is no MOS Roadmap on the Marine Corps Training and Information Management System (MCTIMS), the H-1 Training and Readiness Manuals have no guide, and neither Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron One (MAWTS-1), nor the Company Grade Rotary Wing Monitor (the individual at HQMC who coordinates and issues all O-1 to O-3 Rotary Wing and Tiltrotor aviators their orders) have any written or official career path for an H-1 pilot.

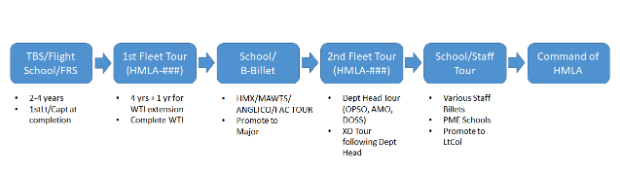

Instead, there is an understood path that each pilot learns by observation during their fleet tours in the HMLAs. Generically, this path is illustrated in the graphic below:

The graphic was developed through firsthand experience and an anonymous poll of company grade officers in three different squadrons. Each was asked if they could describe what a "standard career path" would be if it were in a manual somewhere. The graphic is a composite of the common trends described from a range of individuals ranging from new copilots through WTI captains.

This composited career path is based on one very simple assumption that each aviator sees in their everyday lives in the Fleet. That assumption is: in order to be a Commanding Officer, you must be a WTI. As seen in Table 1, this is not an unfounded assumption (Note: These numbers are conservative as many COs are not correctly listed in MCTFS as 7577 MOS, thus the actual number of non-WTI COs is actually lower than available data presents).

Over 30 years, the Marine Corps has ensured Commanding Officers will be WTIs to the point that only 10% of all HMLA COs over the last decade have NOT been WTIs. This trend has made WTI a de-facto requirement for promotion and command with rare exceptions and this has not gone unnoticed by the company grade masses.

Working backward from this unofficial requirement, being a WTI now becomes a requirement to be the XO or a Department Head (OPSO, AMO, DOSS), the traditional stepping stones to command.

Considering only 3% of H-1 WTI graduates are majors (9 out of 359) since 2005, according to the MAWTS-1 "Skid Newsletters," going to one of the two annual WTI courses during your first fleet tour while you're still learning your job becomes your best, and perhaps only, shot to achieve this unofficial requirement.

In actuality, this may be exactly the career progression model that works best for providing the most competent staff and commanders to the Fleet. Unfortunately, as previously stated, this is the ONLY career path that is communicated and there is no known alternative career path for non-WTIs to be competitive for promotion to O-4 or O-5, let alone to achieve command.

Assuming the non-WTI officers promote to major, their most common path is to fill random staff billets, potentially never returning to flying units until they reach their 20-year retirement.

But even the incentive of a pension after 20 years is waning in effectiveness with the new Blended Retirement System, which gives every Marine a retirement account when they get out regardless of how long they served.

It's no surprise then that aviators, who will have 10-12 years' worth of IRA contributions with government matching funds, would rather market themselves outside the Marine Corps where their income potential is higher and they are potentially able to transfer their IRAs into a company's 401k.

This appears far more enticing than serving in staff positions for 10 more years with limited income growth potential only to get a smaller pension than their predecessors and start a new career in their forties.

At this point you may be thinking, "there's no way the Marine Corps would pigeon-hole their whole fleet of aviators into one career path. There must be other options."

While a logical thought, when asked how a non-WTI's career path is determined and by who, the Rotary Wing Monitor confirmed in an email that there are no official guides or rules and said that a Monitor uses "judgment and experience."

So the careers of non-WTIs are at the discretion of a single Marine at HQMC — who is statutorily a WTI — and whatever their "judgment and experience" happen to be for those Marines. The end result of all of this is that the company grade aviators figure out early on that without becoming a WTI their career is a dead end, or at best a crap shoot, and that with the new BRS, there is limited financial incentive to staying in the Corps.

The final nail in the coffin for these non-WTI aviators are the statistics for how many will ever be given the chance to go to a WTI course.

On average, the Fleet Replacement Squadron graduates 77 newly qualified H-1 aviators (combined total of AH-1 and UH-1). Of those 77, only about 26 can be expected to actually graduate a WTI course. Of note, this is not a question of anyone's qualifications to attend, but rather a statement of the limited throughput capacity of MAWTS-1 to create new WTIs.

Ultimately, 67% of H-1 aviators will never be granted the opportunity to attend a WTI course. When that same 67% recognize this and their lack of a future in the Marine Corps, they will begin to position themselves to leave the Marine Corps with the maximum marketability in the civilian sector.

This dead end career path effect is a constant, major contributor of the company grade exodus and likely does not just affect the H-1 community.