The Inheritance of Power

Monarchy may be rare these days, but nepotism is alive and well.

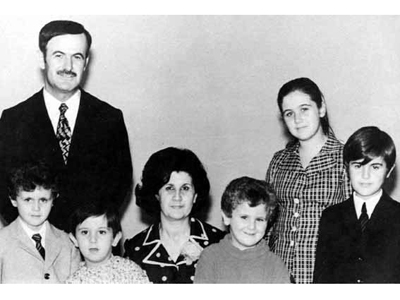

The family of Hafez al-Assad, including young Bashar (bottom left).Although hereditary monarchies with anything more than largely ceremonial roles have dwindled to a only few states, the bequeathing of political power from parent to son or daughter is a remarkably ubiquitous phenomenon. Think about some of the political leaders around the globe we've been hearing most about lately. The big political story out of China concerns recently purged Chongqing party boss Bo Xilai, who is a “princeling,” or son of one of the regime's revolutionary founding fathers. Bo's political career seems to be over, but other princelings remain a prominent part of the Chinese political picture today. Next door in North Korea, we are getting used to a third generation of the Kim dictatorship. Kim Jung-Un has just led celebrations of the one hundredth birthday of his grandfather and regime founder Kim Il-Sung, a physical resemblance to whom apparently is one of Kim Jung-Un's political assets.

The family of Hafez al-Assad, including young Bashar (bottom left).Although hereditary monarchies with anything more than largely ceremonial roles have dwindled to a only few states, the bequeathing of political power from parent to son or daughter is a remarkably ubiquitous phenomenon. Think about some of the political leaders around the globe we've been hearing most about lately. The big political story out of China concerns recently purged Chongqing party boss Bo Xilai, who is a “princeling,” or son of one of the regime's revolutionary founding fathers. Bo's political career seems to be over, but other princelings remain a prominent part of the Chinese political picture today. Next door in North Korea, we are getting used to a third generation of the Kim dictatorship. Kim Jung-Un has just led celebrations of the one hundredth birthday of his grandfather and regime founder Kim Il-Sung, a physical resemblance to whom apparently is one of Kim Jung-Un's political assets.

Among the “republics” of the Middle East, a current focus is on Syria's Bashar al-Assad, who inherited his regime from his father Hafez. In Egypt, if the demonstrators of Tahrir Square had not gotten to Hosni Mubarak first, he might well have bequeathed the presidency to his son Gamal. Elsewhere in the Middle East are most of the few remaining states that are hereditary monarchies in name as well as in fact.

Bequests of political power are certainly not limited to autocracies. In the world's largest democracy, India, the next prospective leader being groomed is Rahul Gandhi, the great-grandson of Indian founding father Jawaharlal Nehru, the grandson of one other Indian prime minister (Indira Gandhi) and the son of yet another (Rajiv Gandhi). Earlier this month, Rahul lunched with a counterpart leader-being-groomed from Pakistan: 23-year-old Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, who is the son of both Pakistan's current president and former prime minister Benazir Bhutto, the grandson of another prime minister, and is himself already chairman of the Pakistan People's Party. On the other side of South Asia in Bangladesh, the prime minister is Sheikh Hasina, who is a daughter of the country's founding father and first prime minister.

The United States is no stranger to such family political legacies. The presumptive presidential nominee of one of the two political parties is the son of a prominent governor and national figure in the Republican Party. The immediate past president was son of a previous president (one of three father-son, or grandfather-son, pairs in the history of the U.S. presidency). In the Democratic Party there have been similar family ties, with the Kennedys probably the best known.

Four possible explanations, or combinations of them, can account for the frequency of political power being inherited by the children of political leaders. One can think of them as affecting different stages in the progeny's personal history, from conception to the progeny's own political career. The first explanation is genetic. It may be a factor, although probably a limited one, given the normal genetic variation even among blood relatives and the uncertainty of linking any gene with political success.

A second explanation involves nurturing during childhood. The children of political leaders grow up in an environment in which political sensibility and associated ambition are more likely to be imparted over the dinner table than they are over other families' dinner tables.

A third explanation involves the opportunities—in education, in business or in politics itself—that open more readily to the offspring of the powerful and famous (and the rich) than they do to others. The biographies of many political scions indicate this is a strong and probably the strongest explanation. Bo Xilai's 24-year-old son Bo Guagua may have now seen his own political prospects sink with those of his father, but his family relationship certainly seems to have opened opportunities for him. Neil Heywood, the deceased Briton who had close ties to Bo Xilai's wife and whose mysterious death is involved in the current controversies about the family, reportedly told others that he had used his influence to get Bo Guagua admitted to the exclusive Harrow School in Britain (where Heywood was an alumnus). The young Bo is now a student at the Kennedy School at Harvard, where officials decline to say whether his family connections played a role in his admission, issuing only the usual boilerplate about a “holistic” approach that takes leadership potential into account. To the extent this third explanation is in play, that is unfortunate from the standpoint of having the most able political leaders rise to positions of power. The differential opportunities are a matter of privilege, not of merit.

The fourth explanation comes into play once the son or daughter is actually vying for political power and wins votes or deference merely because of the name or known family connection. This explanation clearly has a lot of validity as well. We see the phenomenon at work in, among other things, the role that name recognition plays in American elections. And like the third explanation, this is not a good thing if we want the most able leaders to assume power. It represents a further step away from a political meritocracy. To some extent voting for a name may be a low-cost way to make a political choice, but it also is an unreliable way to make it. Those who, for example, voted for George W. Bush on the basis of what they thought of George H. W. Bush's presidency were in for a surprise.

Given how prevalent the inheritance of political power is, across different types of political systems worldwide, this pattern does not seem to be one that would be subject to correction through political or constitutional engineering. And that's too bad.