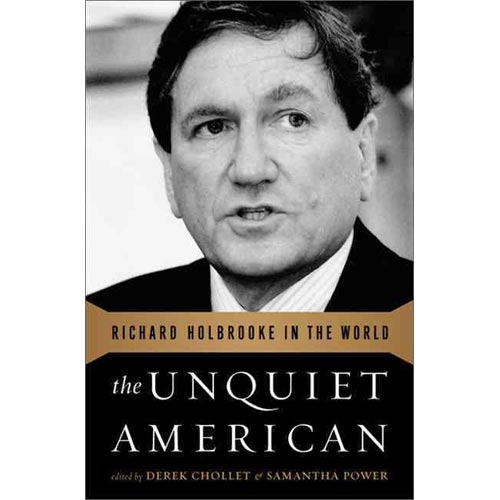

The Hagiography of Mr. Holbrooke

Mini Teaser: Richard “The Bulldozer” Holbrooke left a deep mark on U.S. foreign policy. Yet this collection of essays by his friends and admirers, which gushes with praise, leaves out significant elements of the story.

HOLBROOKE’S LIMITED inclination to change U.S. policy in East Asia, though, was a model of shrewd, insightful statesmanship compared to his performance when he became assistant secretary of state for European affairs during the Clinton years. He acknowledged that he did not have extensive knowledge of European issues or much preparation for that post, and his performance in office demonstrated the adage that a little knowledge can be a dangerous thing.

The quality of the chapters in The Unquiet American regarding that portion of Holbrooke’s career is as frustrating and disappointing as his record. Roger Cohen’s contribution, “Holbrooke, a European Power,” manages to recapitulate nearly every liberal-interventionist cliché concerning both the enlargement of NATO and the Bosnian war, Holbrooke’s two priorities during those years. Derek Chollet’s chapter on the road to the Dayton accords is only marginally better.

Holbrooke, an early and vocal enthusiast for the expansion of NATO, argued that it would stabilize Central and Eastern Europe and, together with the expansion of other Western institutions, especially the European Union, would create the political, security and economic framework for a whole and democratic Europe. Like most proponents of enlargement, he greatly overstated both the importance of enlargement to America’s own interests and the probable benefits to the United States. In his article in the March–April 1995 issue of Foreign Affairs, Holbrooke blithely described America as a European power and argued that the welfare of Central and Eastern European states was vital to this country’s own security and well-being.

As with so many advocates of NATO expansion, Holbrooke misconstrued America’s geostrategic position. The United States is not and never has been a “European power.” It is an external power that has some European interests. That may be a subtle distinction, but it is extremely important. It argues against any legitimate reason for Washington to attempt to micromanage Europe’s affairs, which is what Holbrooke’s approach inevitably entailed. Taking on an assortment of mostly small security clients, several of which have tense relations with neighboring countries, especially Russia, created liabilities for the United States, not assets.

Holbrooke and his allies responded dismissively to prescient warnings that NATO expansion would not only expose the United States to needless security headaches but would also poison relations with Moscow. He and other proponents of expansion audaciously argued that it would actually benefit Russia by creating greater stability on its western flank. Not surprisingly, Moscow saw matters differently—as an attempt by the United States and its allies to take advantage of Russia’s weakness in the initial post–Cold War decade and expand Western power into a traditional Russian sphere of influence.

In his 1995 Foreign Affairs article, reprinted in The Unquiet American, Holbrooke argued, “Expansion of NATO is a logical and essential consequence of the disappearance of the Iron Curtain.” It was, but not in the way he believed. Holbrooke contended that it provided an opportunity to widen European unity based on shared democratic values. Christopher Layne, a professor at Texas A & M University, put it far more accurately in his important book, The Peace of Illusions. The demise of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union, Layne argued, created a power vacuum in Central and Eastern Europe that the sole remaining superpower, the United States, saw an irresistible opportunity to fill. The expansion of a U.S.-dominated NATO was the perfect vehicle to achieve that goal at the expense of the defeated adversary, Moscow. What occurred with NATO expansion, Layne contended, was a real-world application of offensive-realist theory. Specifically, both Washington’s concept of its European interests and its determination to pursue those interests expanded once the Soviet Union no longer constrained U.S. power. The tendency of Holbrooke and his colleagues to cloak NATO’s enlargement in benevolent, moralistic garb was either self-deception or propaganda.

As Russia gradually recovered its economic and military strength, it predictably pushed back against U.S. and NATO ambitions. Moscow’s very effective campaign to regain political influence in Ukraine and the nasty little war waged against Georgia to secure the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia sent a message to Washington that the West’s penetration into Russia’s backyard had reached its limits. It is revealing that the bold talk of extending NATO membership to Ukraine and Georgia, so prominent a few years ago, has largely disappeared.

Because Holbrooke and most foreign-policy opinion leaders in the Democratic Party accepted the fallacy that the United States is a European power, it was not surprising that they wanted decisive U.S. action in Bosnia. Holbrooke insisted that the bloodshed there was taking place “in the heart of Europe.” That characterization was wrong in terms of biology, geography and history. Bosnia and the rest of the Balkans are more accurately viewed as Europe’s infected hangnail, not its heart. Although developments there might be painful and annoying, they are hardly critical to the Continent’s future. Otto von Bismarck aptly observed that the Balkans were not worth the bones of a single Pomeranian grenadier. That was true for continental Europe’s leading power in the late nineteenth century, and it is even truer for a distant power such as the United States in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Not only did Holbrooke and many other prominent American foreign-policy figures overstate Bosnia’s importance to the United States, but their view of the triangular ethnic conflict there was (and largely remains) a simplistic melodrama. “My generation,” Holbrooke wrote, “had been taught in school that Munich and the Holocaust were the benchmark horrors of the 1930s. Leaders of the Atlantic alliance had repeatedly pledged it would never happen again. Yet between 1991 and 1995 it did happen again.”

The equation of the mundane Bosnian civil war with the Holocaust was absurd, but that was the image that drove U.S. policy. The three-year armed conflict, while tragic, produced barely one hundred thousand casualties (including military personnel) on all sides. And yet it became the moral equivalent of Hitler’s extermination of millions of innocents. Advocates of Western intervention augmented that perversion of history with a propaganda campaign that portrayed the complex, multisided fight as a stark case of aggression and genocide that evil Serbs perpetrated against innocent Muslims. (A similar, grotesque interpretation would dominate the U.S. view of the murky Kosovo struggle later in the 1990s.)

Holbrooke’s admirers consider his negotiation (in reality, imposition) of the Dayton accords the crowning achievement of his career. That was true in the sense that his labors ended the armed struggle. But Dayton also created an utterly dysfunctional state from which two of the three antagonistic ethnic groups, the Serbs and Croats (together just over 50 percent of the population), would secede even today if allowed to do so. Moreover, Bosnia remains a perpetual economic basket case and international ward that is no closer to being a viable country now than it was when the Dayton accords were signed in December 1995.

Showing his persistent nation-building tendencies, Holbrooke recognized Dayton’s flaws and grew ever more impatient about them. Derek Chollet notes that Holbrooke described his position as “maximalist” and “worked to forge an agreement that would create a unified, democratic, multiethnic, and tolerant Bosnia.” But his proposed solution—one that a major portion of the foreign-policy community still pushes—was to have the Western powers strengthen Bosnia’s central government by fiat. The assumption of nation builders is that such measures would (somehow) produce the requisite unity to enable Bosnia to function as a cohesive, effective state. It is more likely that such a strategy would intensify simmering ethnic tensions and perhaps even trigger a new war.

PERHAPS THE most telling feature of Holbrooke’s worldview is how closely he adhered to the conventional wisdom of America’s foreign-policy elite that the United States is the indispensible nation in the international system. Some senior Democrats inexplicably regarded Holbrooke as a radical in the 1970s. Richard Bernstein relates that Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter’s national-security adviser, “genuinely disliked Holbrooke, apparently believing . . . that he and his group were ‘left-wing nuts.’” Yet Holbrooke never questioned the prevailing national narcissism about America’s presumedly irreplaceable world role. Neither have most of his colleagues and admirers.

In that sense, there was not much difference between Holbrooke and the neoconservatives that he often criticized. The difference was more of style than substance. Holbrooke, like most liberal Democrats, preferred to have the United States pursue its foreign-policy objectives within a multilateral framework whenever possible. Neoconservatives, in contrast, are usually ostentatious advocates of unilateralism. Not only do such leading neoconservative figures as William Kristol, John Bolton and Charles Krauthammer exhibit contempt for the United Nations, they tend to view NATO and other alliances as being useful only if the other members follow Washington’s policy preferences without a murmur of protest.

Holbrooke and his liberal allies regarded that approach as crude and counterproductive. But he was never a devout multilateralist, much less a member of the quasi-pacifist contingent that backed George McGovern’s presidential candidacy so enthusiastically in 1972. That point became clear on numerous occasions, especially during Holbrooke’s tenure as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations from 1999–2001. Although he argued that the UN could, and often did, serve U.S. interests, he also emphasized that no international body should control Washington’s actions.

Pullquote: Whatever one thinks of his philosophy or his personal style, it can’t be denied that Holbrooke was a powerful figure who left a large mark, for good and ill, on American foreign policy.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review