An Assassin's Creed: Rabin and His Killer

Twenty years after Yitzhak Rabin's assassination, a new book examines the Israeli leader's legacy—and that of his murderer.

Dan Ephron, Killing a King: The Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin and the Remaking of Israel (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015), 304 pp., $27.95.

The best chance for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict appeared to arrive in the early 1990s. A combination of deft international diplomacy and political evolution in the two sides’ leadership led in 1993 to a secretly negotiated agreement—the Oslo accord—between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization that established a partially autonomous transitional mechanism known as the Palestinian Authority. The accord was supposed to lead within five years to the establishment of a Palestinian state recognized by Israel. It didn’t. Instead, the two sides remain locked in a deadly embrace.

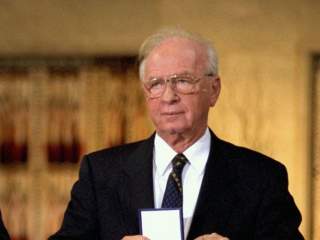

A central figure in the hopeful developments of the 1990s was the prime minister of Israel, Yitzhak Rabin. He had several attributes that qualified him well to play this role. He was the first sabra, or native son, to become prime minister of Israel, having been born in Jerusalem when it was part of the British mandate of Palestine. Rabin’s successful military career, including fighting in Israel’s war for independence, culminated in service as chief of the general staff, a position in which he oversaw Israel’s rout of Arab armies in the Six Day War in 1967. He remained a military officer at heart even after entering politics, always more comfortable talking with generals about security matters than in the other interactions political leaders have to endure.

Succeeding Golda Meir as leader of the Labor Party, Rabin served a first stint as prime minister in the 1970s, when by his own later admission he was insufficiently experienced to do the job well. In 1977, he left office under the cloud of a minor financial scandal dating from earlier service as ambassador in Washington. Then in 1992, more seasoned at age seventy, he led his party to victory over Likud prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, the former Stern Gang terrorist whose electoral defeat was preceded by enough acrimony with the United States that the George H. W. Bush administration withheld loan guarantees to Israel. Over the next three years Rabin led his country through the first steps of implementing the Oslo agreement.

Rabin, whom U.S. envoy Dennis Ross described as the most secular Israeli he had ever met, shared none of the belief held by many Israelis that possession of the territory conquered in 1967 was a fulfillment of Jewish destiny. He could argue that Israel would need parts of the West Bank for security purposes but not because of any sacred status of the land itself. He said that clinging to the territories would mean Israel losing its Jewish majority and—using a term few Israelis dared to speak at the time—turn it into an apartheid state. Rabin had little patience for the settlers, who in turn saw him as a threat. Rabin’s role as peacemaker, and possibly with him any real prospect for completing the process envisioned at Oslo, came to an abrupt end on the evening of November 4, 1995, when a young right-wing Jewish fanatic murdered him after the prime minister addressed a massive pro-peace rally in Tel Aviv.

JOURNALIST DAN Ephron has written a gripping account of the assassination and the political and social currents in Israel surrounding it. A former Newsweek correspondent who reported from Israel at the time, including covering the rally that would be Rabin’s last public appearance, his story has been enriched by voluminous interviews in the subsequent years. Killing a King is an objective and persuasive description of moods as well as facts. As the dual narratives of prime minister and assassin roll toward their convergence point at the site of the shooting, the book becomes a real page-turner.

Ephron begins with Rabin’s trip to Washington for the signing of the Oslo accord, a ceremony featuring a carefully choreographed handshake with PLO leader Yasser Arafat. Ephron continues his story until six months past the assassination, when an Israeli election returned Likud to power. The story thus is not just of a single event, but also of a period of less than three years that marked the high tide of hopes for Israeli-Palestinian peace. The assassination itself was an inflection point: the end of the most significant progress there has ever been toward resolving the conflict (including completion of a detailed implementation agreement, known as Oslo II) and the beginning of the death of the peace process.

Even during that promising era, opposition in Israel to the departure represented by the Oslo agreement was intense. To obtain approval by the Knesset of the accord, Rabin had to rely on votes of Arab-Israeli members, a nettlesome fact that opponents raised ever after as supposedly rendering the decision—and thus the accord itself—less than legitimate. Approval of Oslo II in October 1995 was even closer: a vote of 61-59 at 3:00 a.m. after a long and bitter session of the legislature. Opposition was most determined among, but went well beyond, settlers in the occupied territories. The opposition was impassioned and malevolent, with much of the enmity directed at Rabin himself.

Out of this lethal environment emerged the eventual murderer: a short, intelligent law student of Yemeni extraction named Yigal Amir. Amir’s own extremism was rooted in the combination of an ultra-Orthodox education and day-to-day exposure to the secular side of Israeli society. The discord between these two aspects of his life appeared to radicalize rather than temper him, as explained by a clinical psychologist who examined him years later. A sense of guilt over sensual and material longing curdled within him, providing some of the impetus for extreme acts. This syndrome was remarkably similar to that of another famous extremist son of Yemeni emigrants: Anwar al-Awlaki, who would become a leader of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and whose story is expertly told in Scott Shane’s recent book Objective Troy.

Amir declined the exemption from military service then available to most ultra-Orthodox and did a stint in the Israeli army after completing high school. While in the army his radicalism acquired a more activist tone, in which he disdained as too passive the teachings of his Haredi upbringing that God alone determines the fate of the Jews. Amir had bigger ideas. He favored the idea that Jews needed to take the initiative in figuring out God’s will and implementing it through their own actions. When Amir watched on television the handshake between Rabin and Arafat, he immediately concluded that the Oslo agreement was a disaster for Israel, that Rabin was committing treason by handing over to Palestinians land that God had promised to Jews and that action in response was required.

For the next two years Amir was obsessed with finding ways to undo that perceived act of treason. Some of his initial effort was aimed at assembling a militia—with his principal targets for recruitment being fellow students at Bar-Ilan University—that would disrupt the nascent peace process through attacks and sabotage in Palestinian areas. Gradually his main focus shifted to killing Rabin. How and where to do so—but not whether to commit the crime—was a recurrent subject of conversations between Amir and his brother Hagai, who was more nerdy and technically minded than Yigal and contributed ideas about how a homemade bomb might do the trick.

The title of Ephron’s book derives from a letter that Hagai, after being arrested as an accomplice to the assassination, wrote to his parents in which he self-servingly strove to place the murder in a Jewish tradition of rebellion against apostasy. Yigal had thought even longer and harder than his brother about a religious justification for killing Rabin. He settled finally on a Talmudic principle called rodef, which refers to someone pursuing another person with intent to kill, making it permissible for a bystander to kill the pursuer to save the innocent victim. According to Amir’s logic, Rabin was a rodef because he was in effect killing Jewish settlers. In a further bit of twisted Talmudic interpretation, Amir also considered Rabin to be a moser—a person who turns Jews over to a hostile power and for whom the necessary penalty is death.

A more vivid inspiration for Amir came from the massacre that the American-born physician and settler Baruch Goldstein perpetrated in 1994 at a mosque in Hebron, where he murdered twenty-nine Palestinian worshipers and injured over a hundred more. For hardcore opponents of the peace process, the killing spree demonstrated how even a lone gunman could disrupt that process. Within weeks, Israeli public opinion swung against the idea of forcible removal of settlers; some rabbis pronounced that it was permissible for Israeli soldiers to defy orders for any such removal, and Rabin had to back down from earlier ideas about evicting settlers from Hebron. Amir also saw that Goldstein was lauded in death by the rejectionist community.

PROBABLY THE central lesson of Ephron’s book is that Amir, notwithstanding how his personal experiences helped to make him what he was, only happened to be the triggerman for something much larger than himself. The story of the assassination is not a tale of how a single extremist crossed the threshold into murder but instead of an entire movement that was so hateful and impassioned—and so sure of the justification for its hatred—that murder was a natural consequence. As for the religious rationales, twisted though they may be, three prominent settler rabbis—including the rabbi of Hebron, who at Goldstein’s funeral had praised him as a holy martyr—issued a letter that essentially agreed with Amir’s concept of Rabin as a rodef and a moser. Amir was further emboldened. As he later told the commission that investigated the assassination, “If I did not get the backing and I had not been representing many more people, I would not have acted.”