Getting Strategy and Force Design Wrong: Failing to Appreciate the Weiqi Model

The United States continues to fail to understand China’s conception of containment, which is deeply embedded in Chinese culture and much more nuanced and subtle than current Western thinking.

Following the “long wars” in Iraq and Afghanistan, the U.S. military is in the midst of attempting a major re-orientation toward the Indo-Pacific region. Concurrently, rising neo-isolationism on both ends of the political spectrum and perennial resource allocation decisions between domestic and security programs are generating questions about America’s role in the world and how to achieve strategic ends given limited strategic means. Not surprisingly, domestic politics, COVID, and economic issues have consumed attention spans and resulted in much self-absorption.

Meanwhile, the nation’s adversaries present as having no such self-questioning. To the contrary, they are clearly on the march: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China’s increasingly assertive moves throughout the Indo-Pacific region and beyond, North Korea’s continued development and provocative testing of missiles, Iran’s linkages with and support of both Russia and China, and a host of transnational entities ramping up violence and chaos. In short, multiple state and non-state actors are moving into real and perceived vacuums caused by diminishing American presence.

One essential characteristic of American culture is an unquestioned faith that anything can be improved through the application of more and better technology. This is certainly true of the American way of war, which is highly technocentric, even to the point that capability development now seems to be driving the formulation of strategy rather than the other way around. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Indo-Pacific.

All of this brings us to the issue of how the U.S. military in general, and its sea services in particular, are redesigning themselves to contend with Chinese ambitions in the midst of multipolar global turmoil. It is not an encouraging picture. Old strategic paradigms like “containment” are being dressed in new vocabularies and labeled as “modernization.” The self-deceiving trap of “mirror-imaging” dominates deterrence assessments. Various technologies are being hawked as panaceas for reduced American capabilities.

Current U.S. Marine Corps leadership has so seized on the idea of technologically enabled containment and has divested so much warfighting capability toward that end that it is no longer capable of leading a credible “from the sea” counteroffensive. The essence of its containment concept is emplacing small antiship missile detachments throughout the First Island Chain. Numerous articles have identified significant basing and supportability issues with this concept. Rather than re-visit those valid tactical matters, we want to draw attention to the inherent strategic fallacy undergirding U.S. notions of containment with respect to China.

The United States can take some pride in the conception and implementation of “containment” against the Soviet Union during the Cold War. But, it risks great hubris if it continues to fail to understand China’s conception of containment—a conception deeply embedded in Chinese culture and much more nuanced and subtle than current Western thinking.

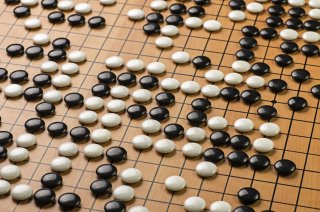

In their desire to explain China’s more sophisticated strategy, some analysts have turned to a Chinese game, weiqi, better known in the West as Go. Weiqi is believed to have been invented over 2,500 years ago. The very word weiqi (pronounced way-kee) means “encirclement board game” or “board game of surrounding.” As such a name implies, skilled players of weiqi develop a deep understanding of both encircling and counters to encircling. Moreover, unlike more Western forms of direct confrontation, weiqi players seek firstly to build strong structures throughout the board and then from multiple positions of strength weaken and suppress enemy structures. The better players shun contact, preferring to parry threats with counter-threats. From the perspective of weiqi, the PRC homeland is but one structure of many being built around the globe.

A recent Atlantic Council-University of Denver study entitled China-US Competition: Measuring Global Influence uses the Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity (FBIC) index to organize data so as to help strategists better understand influence trends over time. Axios extracts three global views (1980, 2000, and 2020) from the study to enable quick tabbing among time frames. These graphics not only highlight increasing Chinese influence and decreasing U.S. influence, but thet also do so in a way that enables us to see the parallels with a sophisticated weiqi strategy: China’s actions over forty years to build influence structures in multiple areas around the globe.

Applying a weiqi model to PRC global initiatives, we can make several observations:

-

While current U.S. attention on Taiwan, China, and the First Island Chain indicates that the United States is focused on a direct approach to containment, the graphics indicate that China is taking a more indirect approach by developing multiple influence structures globally.

-

While U.S. political leaders talk of a “whole of government” approach to international security but struggle to put one into action, the PRC is already acting, taking advantage of lapses in U.S. presence and capabilities.

-

While the graphics help us understand geospatial aspects of Chinese influence structures, we need to be mindful of weiqi applications in other domains, e.g., cyber, critical materials, information, space, chip industry, and so on.

From these observations, we can derive several implications with respect to strategy and force design:

-

The U.S. military’s divestment of current capabilities to invest in unproven future capabilities in essence removes players from the global board and creates vacuums that China and other adversaries are exploiting. It is precisely the wrong business model at the wrong time.

-

China’s 40-year development of overseas influence structures and capabilities aims to outmaneuver any containment strategy based on the First Island Chain. Strategically, Marine Corps elements planning to occupy portions of the First Island Chain are mostly irrelevant even before they deploy. In weiqi terms, they are attempting to occupy what is already a forbidden point—a point surrounded by opposition stones and having no liberties—a rather compelling way of describing the support conundrum of the Marine emplacement of isolated antiship missile detachments!

-

China’s numerous, capable, and growing influence structures overseas will continue to proliferate absent immediate, decisive, and coordinated action by those seeking to forestall Chinese hegemony. Specifically, that intent on preserving some semblance of a more open and free global order must act to increase U.S. presence.

-

The challenges of securing basing rights in the face of Chinese influence structures indicate that multiple naval task forces of varying sizes operating from the seas are essential to countering both Chinese and other adversary attempts to “re-colonize” lesser developed nations.

-

The number, type, and global dispersion of Chinese influence structures mandate a similarly broad-based Western strategy. Within that strategy, the implication for the U.S. naval services is an increased number of naval task force packages capable of multidimensional combined arms operations across the spectrum of conflict—putting more general-purpose, fully capable players on the global game board.

Pulling these points together, we can see that both domestic and Long War distractions have created influence vacuums that China and others have exploited. Divesting general-purpose, sea-based forces has removed potent and relevant players from the board at precisely the wrong time. Worse, developing a specialized, unsupported force for a specific area in an attempt at direct containment is precisely the wrong strategy for the wrong adversary. National strategists need to pull back from a direct, technocentric concept and develop a more sophisticated global strategy that appreciates multi-domain, multipolar influence structures. Civilian leaders need to reverse the current process by which myopic, military force design drives strategy. Rather, the nation needs to restore a coherent process of safeguarding national security by which national strategy drives force design.

Brigadier General Keith T. Holcomb, USMC (Ret.), is a former USMC Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. His last assignment was as Director of the Training and Education Division, U.S. Marine Corps Combat Development Command.

Image: Zerbor/Shutterstock.