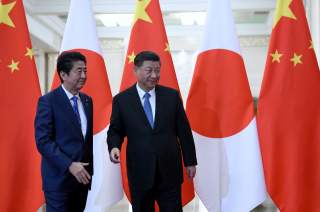

Risks to the Japan-China 'Tactical Detente'

Long-standing tensions between China and Japan thus could reemerge and threaten the current detente. One area of risk that gets less attention is China’s influence operations, which can spark a backlash in Japan and throw relations back off track.

500.com’s new CEO, Pan Zhengming, who replaced the company’s founder, joined the company in 2011 first as CFO to help bring the company public on the New York Stock Exchange. He also heads its Japanese subsidiary, which was established in July 2017. 500.com hosted a symposium in Naha, Okinawa, on Aug. 4, 2017, to discuss casino business opportunities with the help of Masahiko Konno and Katsunori Nakazato, who were consultants to 500.com and among the three arrested on suspicion of providing bribes to the politician Akimoto. The two consultants admitted to the charges. Both CEO Pan and Akimoto (who would go on to be appointed as senior vice minister for integrated resorts three days later) spoke as keynote speakers at the symposium to a crowd of about three hundred attendees from Okinawa’s policy and business circles. Akimoto received an enhanced speaker’s fee of two million yen thanks to his government appointment. At the symposium, Pan announced the company’s plan to invest between 150 and 300 billion yen in Okinawa. Akimoto then visited 500.com in Shenzhen in Dec. 2017 by using 500.com’s private jet.

Konno, the key broker serving as a self-employed consultant, cultivated his business ties in Okinawa by being Koichiro Kokuba’s secretary for four years. Kokuba is the former Chairman of Kokuba-gumi, Okinawa’s largest and most politically-influential construction conglomerate, and died of cancer in April 2019. Konno claims he helped orchestrate the creation of an Okinawan Japan-China friendship association and a party held in Naha on Feb. 3, 2017, where then-Chinese Ambassador to Japan Cheng Yonghua and chairman of the United Front-supported Japan-China Friendship Association, Uichiro Niwa, attended. Katsunori Nakazato, another consultant to 500.com, was an elected parliament member of Okinawa’s Urasoe City since 2013 until he lost for re-election in February 2017.

In 2008, a group of Chinese entrepreneurs founded a nonprofit called Relay China to promote young Chinese business elites and support the interests of the Chinese Communist Party. Konno published a blog post on Nov. 5, 2019, in which he declared that he had helped organize Relay China’s visit to Japan from Oct. 28 to Nov. 2, 2019, with the help of a dozen LDP members. The blog post features a photo of the group’s visit to Japan’s Diet office that he said was arranged thanks to those twelve LDP members. (The post misspells the group’s name, rendering it as “Really China.”) The blog post’s link to Relay China’s website that included pictures of the twelve members was removed but the tabloid Nikkan Gendai published the photo. Among them were politicians Takaki Shirasuka and Shigeaki Katsunuma, whose offices were raided by prosecutors in connection with Akimoto’s arrest. Those two have also visited 500.com in Shenzhen with Akimoto during the same trip in December 2017. Interestingly, Konno has also posted a photo with Nobuo Kishi, Abe’s brother in his February 2019 Instagram post.

The legalization of casinos as part of integrated resorts has been a key part of the “Abenomics” economic policy by Abe, who took office in December 2012 and has become the longest-serving prime minister in Japan’s post–World War II history. Abe initially proposed legalizing casinos in his updated growth strategy “Third Arrow,” which was approved by the Cabinet in June 2014. He said his ruling party sought to pass a law in the extraordinary Diet session in autumn 2014 to legalize casinos to boost tourism before the Tokyo Olympics in 2020. The government aimed to open casinos in three cities by 2020. The legislation kept getting postponed, however, due to a snap election in November 2014, and the Diet session in 2015 focused on passing successful milestone legislation to allow pacifist Japan to exercise the right of collective self-defense. Also, LDP’s coalition partner and a Buddhist political party, Komeito, had been a strong opponent of casino gambling although Komeito is also pro-China.

Public opinion continues to be divided on the issue, with the most recent survey by Jiji in October 2019 showing 60 percent opposing it. It took until December 2016 for the Diet to pass the legislation to lift the ban on casino operations when Akimoto was chairing the lower house Cabinet Committee. The following year, Akimoto was appointed as a senior vice minister at the Cabinet Office to oversee the casino policy from August 2017 to October 2018. Another snap election in September 2017 delayed the Diet to pass the integrated resorts implementation bill until July 2018. Komeito changed its stance to support the bill and explained that they had an obligation to implement a bill that was passed by the democratic process. At the time, Komeito member Keiichi Ishii was the Minister of Land, which is the central regulator of integrated resorts.

The Osaka Prefectural Government, ahead of other local governments, on Dec. 24, 2019, began soliciting applications for casino resort operators with a plan to open them between 2025 to the end of March 2027 except when Osaka hosts Expo 2025 from April to October 2025 as the world expo body asked the government not to open casinos during the expo. The Japanese government plans to issue three casino licenses. Outside of Osaka, Yokohama, Wakayama, and Nagasaki have officially shown interest in soliciting a casino operator. In addition, Hokkaido, Chiba, Tokyo, and Nagoya have shown interest in the government’s survey in September 2019. Japan’s popular tabloid Shukan Bunshun and Nikkan Gendai reported Konno is an illegitimate son of a parliament member of Japan’s Innovation Party Kunihiko Muroi. Japan Innovation Party leader Ichiro Matsui is the current mayor of Osaka.

Arresting a parliament member is rare as Akimoto’s case is the first arrest of a parliament member in ten years since Tomohiro Ishikawa, Ichiro Ozawa’s associate, was arrested on suspicion of violating political-funds rules in January 2010. Since his arrest, Akimoto has left the LDP and has denied the charges. As a bribery case, it is the first arrest in seventeen years since the powerful politician Muneo Suzuki was arrested for receiving bribes ($40,000) from a Hokkaido lumber company in June 2002 during the Junichiro Koizumi administration. Akimoto’s arrest came shortly after Japan’s Diet on November 29 approved the nominations for the country’s new regulatory body Casino Management Committee, which is scheduled to launch on January 7, 2020, as an independent arm of the Cabinet Office. The five board members of the committee is headed by the former inspector general of legal compliance at the Defense Ministry, Michio Kitamura.

The Akimoto casino scandal will continue to unfold and has emerged amid other concerns about China from a case earlier in 2019. In September 2019, respected China scholar Nobu Iwatani, a professor at Hokkaido University, one of Japan’s top national schools, was detained while attending a conference in Beijing. Iwatani was released in November after reportedly confessing to collecting a large amount of “classified information,” but the arrest had already done damage to the China-Japan relationship. A group of 130 Japanese academics specializing in China has signed an open letter, drafted by the normally-sympathetic Japanese Association of Scholars Advocating Renewal of the Japan-China Relationship, demanding that China explain its actions and arguing that the arrest damaged trust between the two nations and was a shock “beyond words.” Since the arrest, many Japanese scholars have canceled research trips to China.

Since 2015, at least thirteen Japanese citizens have been detained in China on various charges, including espionage. But this case was particularly acute for several reasons. First, Iwatani was in Beijing on the invitation of the Institute of Modern History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), a research institution affiliated with China’s State Council, and staying at the facilities provided to him from the institute, raising questions about how it came to be known that he was collecting information and what exactly constitutes “state secrets,” since he was a historian who did research. Given the arbitrariness of the charges and capriciousness of the Chinese legal system, China experts in Japan, who are often naturally fond of China or at least try to remain neutral, have become deeply worried about the implications of Iwatani’s arrest. Also, since Iwatani was from a national university and had previously worked for the Japanese foreign ministry and the defense ministry’s National Institute of Defense Studies and had a reputation for high-quality research and friends in Japanese academia, his arrest carried particular weight. It was seen as an official slap at elite Japan, according to my interviews.

Every China expert I met in Tokyo in December 2019 mentioned Iwatani’s case as a source of concern about the China-Japan relationship, and several experts described the episode as a Chinese “influence operation” that is, again, having a negative effect on Japanese sentiment. The message China is sending to Japan, they told me, was, “We may have a bilateral detente, but we can still do whatever we want,” with some labeling it as “hostage diplomacy.” Citing this case, along with China’s mistreatment of Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang and democracy protestors in Hong Kong, some Japanese wonder if China and Japan are just fundamentally and permanently incompatible, suffering from a “values gap:” Japan is a country with the rule of law and access to legal counsel, while China is a country of rule “by” law where the state is always right; Japan has free speech and free press, while China is a surveillance state with tightly controlled media and no freedom of speech. When Chinese officials speak to their counterparts in Japan, they are speaking different languages, literally and metaphorically. They talk past one another. The backlash among the academic community has been so severe that scholars are calling for Abe to either cancel or scale-back Xi’s state visit in spring 2020.