The Dragon and the Atom: How China Sees Iran and the Nuclear Negotiations

If an agreement is not reached, a question worth asking in hindsight is whether a Chinese role could have been more constructive in the delicate nuclear talks...

Editor’s Note: The following is part four of a new occasional series called Dragon Eye, which seeks insight and analysis from Chinese writings on world affairs. Part one of the series, “What Does China Really Think About the Ukraine Crisis?” can be found here. Part two of the series, “The World’s Most Dangerous Rivalry: China and Japan,” can be found here. Part three of the series, “How China Sees America’s Moves in Asia: Worse than Containment,” can be found here.

Whether or not the current negotiations regarding Iran’s nuclear status lead to an agreement will have enormous consequences for world politics. These consequences will extend well beyond the region itself to impact alignments among the great powers.

The point is often made that Russia’s influence on the process of negotiations is particularly crucial. In that respect, there is no doubt that the grave international crisis in Ukraine in 2014 has significantly complicated the negotiations. If the Iran negotiations end in failure, the turmoil in Kiev and eastern Ukraine may be largely to blame. However, preliminary indications suggest that Moscow has decided not to obstruct, but rather to facilitate, the nuclear negotiations.

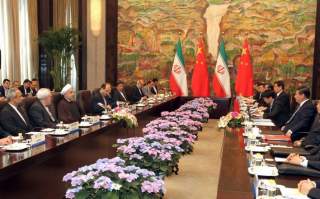

What of Beijing’s stance on the critical nuclear talks? Unlike Russia, China is a major importer of Iranian oil and, moreover, the Middle Kingdom’s influence in the Middle East has been growing by leaps and bounds as its trade with the region has mushroomed over the last decade. This edition of Dragon Eye will seek for a deeper understanding of China’s position on the Iran situation by surveying several recent Mandarin-language writings on the issue.

It’s worth noting at the outset the somewhat extraordinary visit of a Chinese naval flotilla to the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas in September 2014. This event, barely noticed in the Western media, provided the front-page story for 环球时报 [Global Times] on September 23 under the large banner headline: “西方炒作我舰队进波斯湾” [The West Spins Story Concerning Entrance of Our Fleet into the Persian Gulf]. The article, in the main, does report on Western appraisals, quoting one story that has an Iranian commenting that the Chinese ships’ visit is meant to secure China’s major commercial interests in Iran, but does not signify that China had come to defend Iran. Indeed, this visit, the first ever by a Chinese naval squadron to Iran, may most clearly signify just how cautious Beijing has been in dealing with the Iran nuclear crisis over the last decade. In that spirit, this article relates that a Russian warship had visited the same port last year. However, this article also strikes a nationalist chord, quoting an analysis from the Hong Kong paper Ming Pao: the Chinese port visit has “broken America’s blockade … [America] comes to our near seas to stir up problems, so then we will go to the Persian Gulf which [the US] considers important and undertake joint exercises with Iran.”

An interesting scholarly article appeared in the journal 国际政治 [International Politics] in mid-2014 that was “An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of U.S. Sanctions against Iran.” The author observes that because of Washington’s enormous economic power, many countries “被迫” [were forced] to abandon cooperation with Iran. The author somewhat ambiguously places China among many Asian states, including Japan, South Korea and India, that have “大幅减少” [severely curtailed] oil imports from Iran. At that point, the author departs somewhat from political correctness in China, where it is often held that sanctions are wholly detrimental, and the assessment is offered that the sanctions produced “一定冲击” [a certain shock] within Iranian domestic politics, causing the Iranian people to elect the moderate Rouhani. The author goes on to explicitly concede that the sanctions effort succeeded in bringing Iran back to the negotiating table. And yet the article also points out that Tehran has continued to move ahead aggressively with nuclear and missile programs. This analysis, like many other Chinese discussions of the Iran crisis in recent years, holds that the United States does not really have any other realistic means to employ against Iran other than sanctions and, moreover, that Tehran is prepared in case the talks fail. In the end, the author concludes somewhat pessimistically that the sanctions and related negotiations are unlikely to curb Iran’s “地区野心” [wild regional ambitions] and that it is difficult to use economic tools to try to resolve security issues.

A late 2013 article republished in this same journal has the title: “Détente Between the U.S. and Iran: Myth or Reality?” This rather sober analysis does not underestimate the difficulties for both sides and says unequivocally that “U.S.-Iran relations will not reach the point of a ‘Nixon to China’ moment.” This discussion, like the article analyzed above, is rather candid in underlining the severe toll that post-2011 sanctions have taken on the Iranian economy. This Chinese analyst concludes that the Iranian economy urgently requires détente with Washington. But the analysis is not too optimistic regarding an agreement, noting the formidable domestic constraints in both countries that “pours cold water” on the possibility of a rapprochement in U.S.-Iranian relations. “The Iranians will not forget the year 1953 in which the American CIA engineered a coup [in Tehran] … and Americans will not forget that in 1979 its embassy personnel were held hostage for 444 days.” And yet the constructive and rather hopeful tone of the analysis does at least suggest the theoretical plausibility of exploring win-win-win scenarios with respect to the Beijing-Tehran-Washington triangle.

A final article worth consideration in present circumstances was the lead article in the August 2014 edition of the prestigious journal 世界经济与政治 [World Economy and Politics] and carried the title: “On China’s Soft Military Presence in the Middle East in the New Era.” The article begins with the observation that it is reasonable to seek foreign bases as certain reputable Chinese strategists have openly advocated for. The author offers up the example of the search for the missing Malaysian aircraft. Obviously, that search would have been much easier had there been a proximate Chinese base to stage from. But the thesis of the article is to develop a strong contrast between the U.S. model of “hard” military bases in the Middle East that support political objectives such as democracy promotion and counterterrorism and the Chinese model of a “soft” military presence that emphasizes nontraditional security missions and is based on economics. The author does concede that there is in fact a deliberate Chinese strategy to “向西拓展” [expand westward] in both continental and maritime domains. Noting the importance of new Chinese capabilities like the aircraft carrier, as well as important missions such as peacekeeping, humanitarian aid, counterpiracy, search and rescue, in addition to protecting Chinese sea lanes and maritime rights, the author, nevertheless, states emphatically that China will not challenge the leadership of other great powers. The author states, moreover, that China’s soft military presence in the Middle East can support China’s “创造性加入” [creative intervention] in global hot spots.

These articles represent only a small sliver of a large discussion about the Middle East that is ongoing in Chinese foreign-policy circles. However, a preliminary conclusion can be drawn from this very small literature review that Beijing seems reasonably positive with respect to the possibility of a near-term nuclear deal between Iran and the West. Moreover, the dark scenario in which Beijing and Tehran significantly upgrade their strategic ties to include larger scale arms transfers, bases and so on remains far-fetched, even as some reports suggest that Beijing’s imports of oil from Iran may have significantly increased during 2014. Still, the even darker scenario in which Beijing seeks to benefit from Western tensions or even a military conflict with Iran also seems to find hardly any substantiation in these Chinese discussions, fortunately.

In May 2013, the eminently wise TNI Middle East blogger Paul Pillar suggested that both the Middle East and China could benefit from an increased role for Beijing in peacemaking in this blood-soaked region. If an agreement is not reached between Washington and Tehran, a question worth asking in hindsight would be whether a Chinese role could have been more constructive in the delicate nuclear talks and how U.S. policy has facilitated that result or to the contrary, as the case may be. Indeed, U.S. diplomats need to avoid the present tendency toward zero-sum thinking in geopolitics and instead may consider how a Chinese naval squadron in the Persian Gulf for the first time in modern history could actually be a stabilizing factor in the present nuclear negotiations and for future Middle East security more generally.

Lyle J. Goldstein is Associate Professor in the China Maritime Studies Institute (CMSI) at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, RI. The opinions expressed in this analysis are his own and do not represent the official assessments of the U.S. Navy or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Image: Iran president website