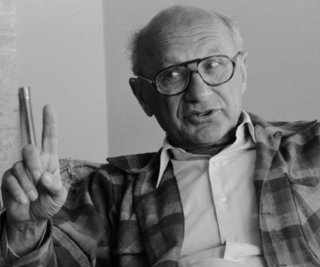

The Visionary Milton Friedman and China

In keeping with Friedman’s teachings, the Chinese economic miracle confirms that greater prosperity for the people can only be achieved by expanding private property rights and promoting the free market.

U.S. economist Milton Friedman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976. Prior to the prize announcement, almost a month before it was made, Mao Zedong died. Four years after Mao’s death, Friedman visited China for the first time. Upon his return, he predicted that China had the potential to mirror the rapid economic growth seen in Japan and Germany after World War II. At the time, Friedman was almost alone in making such a clearly positive assessment of China’s economic future.

It is important to remember that in 1980, 88 percent of the Chinese population was still living in extreme poverty. Just four decades later, the rate of extreme poverty has fallen to less than 1 percent. Never in history have so many people escaped from poverty in such a short period of time. How did this happen? That is one of the biggest questions of the century and the answer to it depends largely on how a person views the role of the market and the state.

In 1980, the situation was still very unclear. Friedman was surprised when he discovered during his stay in China that the works of Friedrich August von Hayek had been translated into Chinese and were quite popular. There were articles about Hayek in Chinese economics journals and Friedman was pleased to discover that some Chinese economists already owned the recently published Japanese edition of his book Free to Choose. He was also delighted by the fact that a Chinese translation of his book was also being prepared. From his memoirs, it is clear that Friedman was torn between great hope on the one hand and skepticism on the other. In a 1980 report, he wrote that China’s economic reforms were moving in the right direction, before adding: “But the test of whether they will be carried out and what their effects will be is still for the future.” At the time, he was convinced that China would make short-term progress while retaining doubts about the prospects for long-term reform.

Friedman visited China for a second time in 1988 at the same time as the libertarian Cato Institute organized a conference in Shanghai—a remarkable event in and of itself. Friedman gave a speech at the conference and did not hide the fact that the transition from a planned economy to a market economy would also involve considerable costs. But, he added: “It is a tribute to the current leaders of China that they are engaged in a serious effort to make the transition. The Chinese people would be the main but by no means the only beneficiaries of the success of this effort. All the people of the world would benefit.” These were almost prophetic words. After all, without the rapid growth of the Chinese economy, there is no way the world economy would ever have experienced such positive growth. Everyone knows that China is the engine of growth that drives the world economy, but Friedman identified the country’s potential as early as 1988.

Friedman’s optimistic stance was encouraged by a conversation he had with the then-general secretary of the Communist Party, Zhao Ziyang, whom he described as having a “real understanding of what it means to free the market.” In his autobiography, Friedman writes that his two-hour conversation with Zhao Ziyang made a very positive impression: “He displayed a sophisticated understanding of the economic situation and of how a market operated. Equally important, Zhao recognized that major changes were needed and evidenced an openness to change.”

When he visited Shenzhen, he was impressed by the fact that this small port city of just six thousand people in 1982 had grown into a vibrant city with five hundred thousand inhabitants. Shenzhen was China’s first special economic zone and more closely applied the principles of the market economy than countries in Europe or even the United States. When I visited Shenzhen in 2018 and 2019 to lecture at the university, I was impressed by this metropolis of 12.5 million inhabitants and its incredible entrepreneurial spirit.

In 1993, Friedman visited China for a third time. Friedman’s impressions were more skeptical on this occasion than had been the case in 1988, and although he was again able to meet the General Secretary of the Communist Party, Jiang Zemin, their exchange of views was very one-sided: Friedman only managed to speak for ten minutes while Jiang Zemin took over the rest of their meeting and spoke for a total of 45 minutes.

Friedman now doubted whether China would continue along the path it had embarked upon with the introduction of private property rights and the steps it had taken to introduce free-market principles.

In the West today, there is a massive misunderstanding about the factors that have most contributed to China’s enormous economic success. Many people believe that China has discovered a “Third Way,” a path between socialism and capitalism. Many even believe that China’s incredible success has only been possible because the state has retained such a strong influence over the economy. In 2018, I traveled to Beijing and met Zhang Weiying, a Chinese economist who has been influenced by the teachings of Hayek and Friedman. He strongly disagreed with the prevailing interpretation, stressing repeatedly that the only reason the state still plays such an important role in modern China is because of the country’s recent history, which saw the state controlling almost 100 percent of the economy. But China’s economic success over the last four decades is entirely based on the fact that the role of the state has been gradually reduced.

During our conversation, Zhang Weiying repeatedly stressed that “China’s economic rise is not because of the state, but in spite of the state.” Friedman would certainly have agreed. The brilliant economist was one of the first to accurately predict China’s future. Today, as confirmed by a working paper from the World Economic Forum, the private sector is the driving force in China: “China’s private sector . . . is now serving as the main driver of China’s economic growth. The combination of numbers 60/70/80/90 are frequently used to describe the private sector’s contribution to the Chinese economy: they contribute 60% of China’s GDP, and are responsible for 70% of innovation, 80% of urban employment and provide 90% of new jobs. Private wealth is also responsible for 70% of investment and 90% of exports.”

Friedman was, of course, critical of the fact that China did not introduce political freedoms to match its economic freedoms. In Chile, he had seen free-market reforms help to end the country’s military dictatorship. He hoped that increased economic freedom would also lead to greater political freedom in China. Despite his hopes for greater political freedom, however, he remained skeptical, and rightly so, as we know today. In keeping with Friedman’s teachings, the Chinese economic miracle confirms that greater prosperity for the people can only be achieved by expanding private property rights and promoting the free market.

Rainer Zitelmann is a historian and sociologist and the author of the book The Power of Capitalism.

Image: Reuters