Will U.S.-China Relations Ever Recover?

There is certainly scope for Beijing and Washington to learn how to avoid unintended additional provocations and to develop methods to limit unwanted crisis escalation. Unfortunately, however, our previous notion of normal U.S.-PRC relations may have become obsolete.

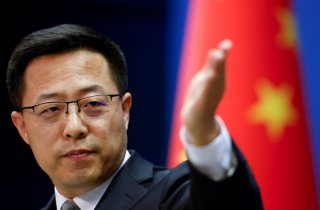

Relations between the United States and People’s Republic of China (PRC) have been in a serious downturn since at least March 2020, when Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Zhao Lijian infamously blamed the pandemic on U.S. soldiers and U.S. president Donald Trump called Covid-19 the “Chinese virus.” Nearly two years later, observers are understandably looking for the first signs of recovery in a relationship in which both sides recognize the value of cooperation and the dangers of unbridled tensions. But they may be looking in vain.

After the U.S. and PRC senior officials held a contentious meeting in Alaska in March 2021, the virtual summit between Joe Biden and Xi Jinping in November was more business-like. Nevertheless, the summit did not produce the hoped-for breakthrough by de-escalating tensions. In the days afterward, Chinese warplanes continued to buzz Taiwan, continuing a months-old campaign of military pressure. Likewise, in December, the Biden administration announced a diplomatic boycott of the Beijing-hosted Winter Olympics, and Biden convened the Summit for Democracy. Both actions drew sharp criticism from the Chinese government.

But this back-and-forth behavior is not unusual. U.S.-PRC relations in the post-Mao Zedong era have generally followed a cyclical pattern, with setbacks giving way to periods of recovery. The Tiananmen Massacre of June 1989 caused Washington to hit China with criticism and sanctions, to which Beijing responded angrily. Most of the sanctions, however, were soon lifted or not enforced. China kept its most-favored-nation trade status and U.S.-China business boomed in the 1990s.

Another example is the collision of a U.S. EP-3 surveillance aircraft with a Chinese J8 fighter over international waters near Hainan Island in 2001, which caused the death of a Chinese pilot and led to the temporary detention of the U.S. crew and incited a bilateral crisis. Both sides blamed the other for the crash: the Chinese objected to the damaged U.S. aircraft landing at a Chinese airfield without permission while the Americans accused the Chinese of wrongfully holding the crew hostage. Nevertheless, four years later senior U.S. officials stated that the U.S.-China relationship was at its best in three decades.

A third example is when U.S. aircraft mistakenly dropped bombs that struck the PRC embassy in Belgrade and killed three Chinese nationals in 1999. The Chinese government believed this strike was intentional and later demanded compensation but decided not to fundamentally alter relations with the United States. Two years later, China joined the World Trade Organization with Washington’s backing.

Thankfully, bilateral downturns have been brief. Historically, there was a consensus in both countries that preserving a constructive relationship was worth enduring a few adverse developments. But recovery from downturns today is less certain because the underlying circumstances influencing U.S.-China relations have changed.

Until recently, the United States enjoyed a huge advantage over China in military and economic power, and this contributed to stable relations.

To elaborate, China was not in a position to do serious harm to the United States. Thus, Washington had the luxury of taking a relaxed approach to China’s military build-up, the early years of China’s growing trade surplus with the United States (which began in the late 1980s), China’s South China Sea claims, a standing threat to force reunification with Taiwan, and violations by China of its international commitments. Accordingly, U.S. policy toward China was not fully mobilized for competition and deterrence, but included efforts to encourage Chinese integration into international organizations and regimes with the intention to avoid the appearance of “treating China like an enemy.”

For Beijing, the power imbalance that remained heavily in America’s favor in the post-Cold War period meant it was not feasible for China to directly challenge the U.S. strategic position in eastern Asia, nor to impose Beijing’s will on peripheral states acting against the Chinese agenda under the cover of the U.S.-sponsored regional order. As acknowledged by Deng Xiaoping’s famous twenty-four-character foreign policy orientation, this was a time to build up China’s strength through trade and investment with the United States and to avoid confrontation unless the United States threatened a vital Chinese interest. Prior to Xi assuming paramount leadership, Beijing seemed cautious about policies that might alarm other states into forming a defensive anti-China coalition—all of this mollified U.S. concerns about specific PRC intentions.

Today, however, that power differential has greatly diminished. Although China is not militarily superior to the United States, the People’s Liberation Army is now strong enough to inflict daunting costs on U.S. forces in a scenario where U.S. forces are trying to deny the Chinese a regional military victory. Further, China’s massive economic importance gives it strategic leverage. Beijing can weaponize its trade to coerce countries not traditionally aligned with China to support its objectives in political disputes, as with South Korea and the THAAD issue in 2016-2017. Even more troublesome is the fact the PRC has a reasonable chance of seizing leadership in the development of key future technologies such as artificial intelligence, green energy production, quantum computing, and cutting-edge medicines.

China approaching the level of a peer competitor resets the relationship. Washington now views the PRC as a current rather than as a future potential adversary. Preparing for possible war and avoiding cooperation that might be to China’s strategic advantage has become an urgent concern for the United States. This antithetical approach works against a return to the historic kind of relationship that prevailed prior to the United States losing its strategic cushion.

Furthermore, the domestic political atmosphere in both countries is increasingly inimical to a return to the old bilateral normal.

Although Beijing calls on Washington to “manage differences” and remove the restrictions on U.S. wealth and technology flowing into China, Beijing is also moving beyond the old relationship. In support of its primary goal of maintaining a monopoly over Chinese political power, the Chinese Communist Party has stoked public expectations that China is now a great power and can impose its agenda internationally. Whether factually accurate or not, the Chinese government now emphasizes a narrative where China is ascendant and the United States is declining.

The diminution of its power gap with the United States emboldens China to push for hastening the transition of leadership in the Asia-Pacific region from Washington to Beijing, and even to treat the United States as an inferior. Manifestations include “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy, Politburo member Yang Jiechi telling senior U.S. officials that “the United States does not have the qualification to ... speak to China from a position of strength,” and PRC officials presenting the visiting U.S. deputy secretary of state with lists of demands to cease U.S. policies that China dislikes.

Although the PRC’s posturing plays to the domestic audience, it is also reflected in China’s external behavior, indicating this is not merely a veneer of affected bravado. From the Sino-Indian border to the East China Sea, the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, and beyond, intimidation has become the default mode of Chinese foreign policy. This underscores the government’s conclusion that the period of low-profile build-up, to which Deng’s advice applied, is over. As a consequence, the ground beneath the U.S.-China relationship has shifted.

With highly-publicized U.S. movement toward economic decoupling, the bitter bilateral acrimony related to the Covid-19 pandemic, U.S. sanctions and criticism of China over Xinjiang and Hong Kong, the emergence of a more robust Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (the Quad, which Beijing decries as an “Indo-Pacific NATO”), and U.S. government statements of support for Taiwan, the Chinese believe attempts to “contain” China are intensifying. To Beijing, Washington is obstructing China from accumulating national power and ascending to regional leadership and global prominence.

To the extent Chinese believe the United States is committed to a policy of opposing the fulfillment of vital Chinese interests, suspicion and competition will inevitably dominate the relationship. This trend reverses the pre-Xi norm of a mostly cooperative relationship with pockets of friction.

In the United States, loss of faith in liberalism allows for a more clear-eyed view of the natural antagonism between China and the United States. Further, U.S. corporate leaders, senior bureaucrats, and politicians argue that deep economic engagement would cause China, an authoritarian and highly mercantilist state, to liberalize its economic and political systems. This belief operated as a unilateral confidence-building measure, assuring Americans that China was destined to be a “stakeholder” in a U.S.-sponsored system of international norms and institutions. It was a crucial section of the foundation of the post-Cold War U.S.-PRC relationship. Sadly, Xi demonstrated convincingly that increased U.S.-fed economic development was not making China more liberal, either internally or externally. Americans are now primed to view China as an adversary; Indeed, it is one of the few issues around which there is a strong national consensus. In fact, both major political parties boast of being tough on China.

Today, the U.S. business community is not as forceful or effective a champion of good U.S.-China relations as it previously has been. U.S. businesses have not abandoned China wholesale, but increasingly they are as likely to complain about unfair or exploitative treatment by the Chinese government as they are likely to campaign for friendly relations. They point to conditions such as Chinese protectionism, discrimination against foreign businesses, threats to data security, and forced technology transfer that are worsening the environment for U.S. companies in China. Industries that call for overlooking bad behavior by the Chinese government in the interest of profits are subject to public shaming.